Twenty years after the great age of sixties Blues-Rock, sociologist Philip Ennis describes the death of the era by pointing to several events which he feels best symbolize the period. He lists: the death of Brian Jones, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the disbanding of the Beatles..., and then finishes with, By 1969, even the Haight was dead: ........, but in the middle of his list of iconic symbols, he makes a statement which doesn't seem to fit.

He says, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was at the end of its creative life. He is implying the false notion that the Butterfield Blues Band has somehow run out of creative ideas at this time. The truth is that by 1971, the Butterfield Blues Band is still a creative force, but about to become another victim of the changing economic expectations of the Rock industry.

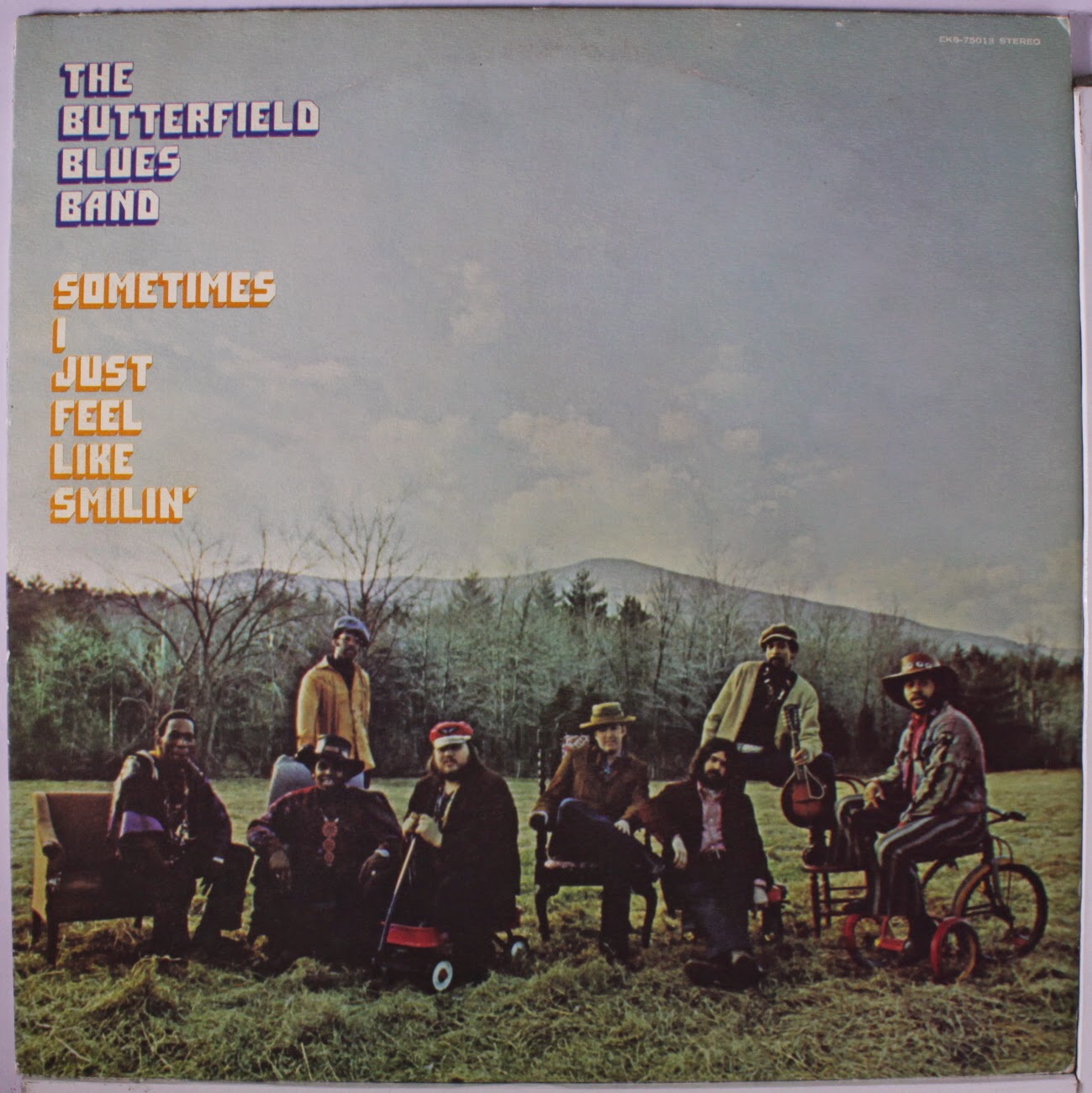

In August of '71, Elektra releases the Butterfield Blues Band's seventh, and final album, Sometimes I Just Feel like Smilin', serving as both a final creative expression from the band as well as a symbolic tombstone for an important personality in the development of a generation's music. In the coming years, historians, music critics, and fans will try to simplify the reasons for the end of the Butterfield band, but as is the norm in history, the complex reality is most often a victim of neglect. One theory can be put to rest though, we only need to listen to the album to conclude that the Butterfield Blues Band is not lacking in creative energy. In addition, they aren't experiencing a massive decrease in audience support either, only a leveling, and they are still making money for Elektra, Albert Grossman, and concert promoters.

In August of '71, Elektra releases the Butterfield Blues Band's seventh, and final album, Sometimes I Just Feel like Smilin', serving as both a final creative expression from the band as well as a symbolic tombstone for an important personality in the development of a generation's music. In the coming years, historians, music critics, and fans will try to simplify the reasons for the end of the Butterfield band, but as is the norm in history, the complex reality is most often a victim of neglect. One theory can be put to rest though, we only need to listen to the album to conclude that the Butterfield Blues Band is not lacking in creative energy. In addition, they aren't experiencing a massive decrease in audience support either, only a leveling, and they are still making money for Elektra, Albert Grossman, and concert promoters.

Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' is another one Butterfield's albums which is often overlooked by fans, and underrated by critics. However, it does have weak moments as in the use of Rod Hicks (1000 Ways), and Ralph Wash (Pretty Woman) as lead vocalist. Neither Hicks nor Wash possess the vocal dynamics to be awarded a place fronting a band as powerful as the Butter band. Also, the use of the two bland lead singers presents a frayed focus for listeners, the same error Butterfield makes with In My Own Dream in 1968. (Most bands with a scattered focus do not capture as much success as bands with a single voice, The Band is one example.)

The other weakness of the album can be found in some of the arrangements. Throughout the latter half of the sixties, Butterfield plays a significant role in the introduction of Rhythm & Blues artists, and their music, to the fresh ears in mainstream Rock, but by '71, his contributions are forgotten. So, when he records a mere duplication of Ray Charles' Drown in My Own Tears or Albert King's Oh Pretty Woman it comes off as trite - lazy behavior for a band of Butterfield's stature.

The other weakness of the album can be found in some of the arrangements. Throughout the latter half of the sixties, Butterfield plays a significant role in the introduction of Rhythm & Blues artists, and their music, to the fresh ears in mainstream Rock, but by '71, his contributions are forgotten. So, when he records a mere duplication of Ray Charles' Drown in My Own Tears or Albert King's Oh Pretty Woman it comes off as trite - lazy behavior for a band of Butterfield's stature.

However, these are minor criticisms next to the album's strengths. Producer Paul Rothschild and Butterfield have added an powerful group of soulful background singers in Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Venetta Fields, and Oma Drake. Their addition to the band separates the album's music from all of the other horn bands which are springing up by the early seventies. The singers also allow for the addition of Gospel, Soul, and Funk influences into their music. Decades later, the album still sounds like a fresh blend of yeasty Americana music, with a soundscape reminiscent of a Phil Spector's, wall of sound.

Butterfield shows up as a much stronger songwriter on this album too. He has credits in over half of the nine compositions, all of them well crafted. Two of those compositions Night Child and Song for Lee should be recognized as the first Jazz/Rock instrumentals which feature a harmonica.

Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' even has the most pop oriented song ever recorded by any of the Butter bands. Butterfield and his wife Kathy, are credited to Blind Leading the Blind, a catchy Gospel flavoured shuffle. Unfortunately, it proves to be no match for hits by other top 70's horn bands: Chicago Transit Authority's new album 111 reaches # 2, Lighthouse's single One Fine Morning peaks at # 2, Blood Sweat and Tears' single Go Down Gamblin' #10, and even newcomers Edgar Winter's White Trash's first album is working its way up to # 70 on the album charts. The lack of promotion from Elektra is part of the reason Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' is struggling to hold on to #124 on the album charts.

It is easy to point to the lack of mainstream pop hits as the reason for the decline of the Butterfield Blues Band, but during the sixties, and early seventies, it isn't unusual for bands to have very successful careers with no major mainstream hits. In fact, fans of artists associated with the counter culture movement often consider the position as a badge of honor. However, that attitude is changing. By the early '70's Rock is becoming a huge industry feeding off massive outdoor festivals and album sales. Consequently, record labels, promoters, and artist managers are expecting bigger pay offs for their investments.

It is easy to point to the lack of mainstream pop hits as the reason for the decline of the Butterfield Blues Band, but during the sixties, and early seventies, it isn't unusual for bands to have very successful careers with no major mainstream hits. In fact, fans of artists associated with the counter culture movement often consider the position as a badge of honor. However, that attitude is changing. By the early '70's Rock is becoming a huge industry feeding off massive outdoor festivals and album sales. Consequently, record labels, promoters, and artist managers are expecting bigger pay offs for their investments.

So, why does the Butterfield Blues Band end? There is no key breakdown in personnel as happens within the Beatles, or death of the voice of a band as is the case with Morrison or Joplin. There is none of that dynamic taking place in the Butter band. It seems that most plausible scenario is one which begins, and ends with one word, money.

Around 1970, Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman is spending most of his time away from his New York City management offices, and instead, focusing his energies on building his entertainment empire in Woodstock, New York. Some sources suggest that he makes this retreat because of the death of Janis Joplin, but this seems unlikely as a key reason. He is disappointed by the Blues singer's senseless departure, but he also collects on the 200K life insurance policy he purchases before her death. Grossman seems too calculating to succumb to such intense emotions. Regardless, he does retreat upstate, and consequently his business interests in the city suffer. This will prove to contribute to the end of Butterfield's band, but also push Butterfield's career in new, and more positive directions.

Around 1970, Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman is spending most of his time away from his New York City management offices, and instead, focusing his energies on building his entertainment empire in Woodstock, New York. Some sources suggest that he makes this retreat because of the death of Janis Joplin, but this seems unlikely as a key reason. He is disappointed by the Blues singer's senseless departure, but he also collects on the 200K life insurance policy he purchases before her death. Grossman seems too calculating to succumb to such intense emotions. Regardless, he does retreat upstate, and consequently his business interests in the city suffer. This will prove to contribute to the end of Butterfield's band, but also push Butterfield's career in new, and more positive directions.

In addition, Butterfield's label Elektra Records has made a complete transition from recording acoustic folk in the early sixties to electric mainstream pop artists. The change is proving lucrative for them as they now employ some substantial revenue generators: the Doors, Bread, and Badfinger to name a few. These assets are definitely making more money for them than the Butterfield Blues Band. The band has not become a financial liability for them yet, but the label is beginning to neglect their investments in the band.

.jpg) So, the end of the Butterfield Blues Band seems to be best described as a product of business the dynamics between Grossman & Elektra. Butterfield is just an artist caught in the middle. During this period he is about to be faced with decisions he does not want to make. He just wants to carry on creating music, but whether he likes it or not Grossman presents him with this ultimatum:, disband your group, leave Elektra, and come with me or face extinction. Grossman is starting his own label, Bearsville Records, and negotiates a distribution deal with Warner. He wants Butterfield to be one of his first artists, and so secures him a $250,000 deal. (a large sum of money in '71)

So, the end of the Butterfield Blues Band seems to be best described as a product of business the dynamics between Grossman & Elektra. Butterfield is just an artist caught in the middle. During this period he is about to be faced with decisions he does not want to make. He just wants to carry on creating music, but whether he likes it or not Grossman presents him with this ultimatum:, disband your group, leave Elektra, and come with me or face extinction. Grossman is starting his own label, Bearsville Records, and negotiates a distribution deal with Warner. He wants Butterfield to be one of his first artists, and so secures him a $250,000 deal. (a large sum of money in '71)

The dilemma for Butterfield is if he stays with a Elektra, he will probably lose Grossman as his manager, and his future with the label is not looking positive anyway. As Nick Gravenites describes the situation, Albert had made Paul a huge record deal with Warner Brothers, which was affiliated with Grossman’s Bearsville label, He told him, I’ll give the money to you, but I won't give it to (the other band members). If you take it - just you can keep it. If you split it with the band, they've got to pay off their debt to me. Paying their debt consisting of expenses typically covered by management would have wiped out the funds from Butterfield’s deal, .... Paul was begging pleading with him not to do that, says Gravenites. In the end, though, Paul took the money. If you are standing on the outside of this decision, the solution may appear simple, but for Butterfield it is about more than just money, there is security, attachment to Grossman, and loyalty to his band members, and family to consider.

In addition to all of the business issues facing him, Butterfield also has personal considerations too. He has been living in Woodstock for three years now, remarried, has a young son, Lee, a comfortable house with several acres on Highway 212, a couple of horses, two dogs, and many musician friends in the area. (the photos for the album cover are done in his backyard.) Most of his domestic stability is a result of his reputation as a musician, a bandleader, and seven years on the road. There must be times when he feels isolated, relieved, contented, and yet anxious about the potential of being unemployed with no band to call his own. The whole emotionally exhausting experience must leave him caught somewhere between smiling, and wishing for better days.

In addition to all of the business issues facing him, Butterfield also has personal considerations too. He has been living in Woodstock for three years now, remarried, has a young son, Lee, a comfortable house with several acres on Highway 212, a couple of horses, two dogs, and many musician friends in the area. (the photos for the album cover are done in his backyard.) Most of his domestic stability is a result of his reputation as a musician, a bandleader, and seven years on the road. There must be times when he feels isolated, relieved, contented, and yet anxious about the potential of being unemployed with no band to call his own. The whole emotionally exhausting experience must leave him caught somewhere between smiling, and wishing for better days.

Every artist's career conforms to its own trajectory, the commonality is that they all rise from obscurity, peak, and begin a descent back into obscurity. For pop bands the process usually takes about five years, but blues bands, it's only two years. Most of the time it has nothing to do with the creative energy, or the quality of music, but rather situations which are out of their control. The trick is that once an artist reaches their peak, they need to drag out the decline as long as possible. The Rolling Stones have been coasting down for thirty years, and the Beatles even longer. In the case of the Butterfield Blues Band's career, it seems to peak with The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw, and then declines to reach its end with Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin'.

In '72, Elektra will release Golden Butter: The Best of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. It is testament to the financial impact the band has on Elektra Records; most of the double album is devoted to the first two albums, offers only minor recognition to everything else the Butter Band records, and only whispered lip service to the other contributions he makes to popular music in the 1960s. It peaks at #136 on the album charts. In addition, U.K. label Red Lightin' releases An Offer You Can't Refuse (see post #3) in 1972.

In '72, Elektra will release Golden Butter: The Best of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. It is testament to the financial impact the band has on Elektra Records; most of the double album is devoted to the first two albums, offers only minor recognition to everything else the Butter Band records, and only whispered lip service to the other contributions he makes to popular music in the 1960s. It peaks at #136 on the album charts. In addition, U.K. label Red Lightin' releases An Offer You Can't Refuse (see post #3) in 1972.

The irony of the end of the Butterfield Blues Band is that for the remaining life of Paul Butterfield's career, he will be constantly measured by the what he accomplishes in his original Butterfield Blues Bands. The one relief for him in his the new phase of his career is that he will never have to answer interview questions requesting an explanation of why his music isn't blues. That question must have wiped the smile from his face a few times.

the Butterfield Blues Band : Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin'

1) Play On, 2) 1000 Ways, 3) Pretty Woman, 4) Little Piece of Dying, 5) Song For Lee, 6) Trainman, 7) Night Child, 8) Drown In My Own Tears, 9) Blind Leading The Blind.

Paul Butterfield: Vocal, harmonica, (piano on Blind Leading The Blind), Gene Dinwiddie: Tenor & soprano saxophone, flute, tambourine, (vocal on Drowned In My Own Tears), Rod Hicks: Bass, (vocal on 1000 Ways), Ralph Wash: Guitar, (vocal on Pretty Woman), Dennis Whitted: Drums, Bobby Hall:, Conga, bongos, Ted Harris:, Piano on Night Child, and Play On, George Davidson: - Drums on Night Child, and Play On, Trevor Lawrence: - Baritone saxophone, David Sanborn: Alto saxophone, Steve Madaio: Trumpet, Big Black: Congas.

Background Vocals: Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Venetta Fields, Oma Drake, Paul Butterfield, Rod Hicks, Ralph Wash, Gene Dinwiddie.

Producer: Paul Rothchild, Recording Engineers: Fritz Richmond, Bruce Botnick, Marc Harmon. Re-mixing Engineer: Fritz Richmond. Mixing: Todd Rundgren, Album Photography: Barry Feinstein.

He says, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was at the end of its creative life. He is implying the false notion that the Butterfield Blues Band has somehow run out of creative ideas at this time. The truth is that by 1971, the Butterfield Blues Band is still a creative force, but about to become another victim of the changing economic expectations of the Rock industry.

In August of '71, Elektra releases the Butterfield Blues Band's seventh, and final album, Sometimes I Just Feel like Smilin', serving as both a final creative expression from the band as well as a symbolic tombstone for an important personality in the development of a generation's music. In the coming years, historians, music critics, and fans will try to simplify the reasons for the end of the Butterfield band, but as is the norm in history, the complex reality is most often a victim of neglect. One theory can be put to rest though, we only need to listen to the album to conclude that the Butterfield Blues Band is not lacking in creative energy. In addition, they aren't experiencing a massive decrease in audience support either, only a leveling, and they are still making money for Elektra, Albert Grossman, and concert promoters.

In August of '71, Elektra releases the Butterfield Blues Band's seventh, and final album, Sometimes I Just Feel like Smilin', serving as both a final creative expression from the band as well as a symbolic tombstone for an important personality in the development of a generation's music. In the coming years, historians, music critics, and fans will try to simplify the reasons for the end of the Butterfield band, but as is the norm in history, the complex reality is most often a victim of neglect. One theory can be put to rest though, we only need to listen to the album to conclude that the Butterfield Blues Band is not lacking in creative energy. In addition, they aren't experiencing a massive decrease in audience support either, only a leveling, and they are still making money for Elektra, Albert Grossman, and concert promoters.Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' is another one Butterfield's albums which is often overlooked by fans, and underrated by critics. However, it does have weak moments as in the use of Rod Hicks (1000 Ways), and Ralph Wash (Pretty Woman) as lead vocalist. Neither Hicks nor Wash possess the vocal dynamics to be awarded a place fronting a band as powerful as the Butter band. Also, the use of the two bland lead singers presents a frayed focus for listeners, the same error Butterfield makes with In My Own Dream in 1968. (Most bands with a scattered focus do not capture as much success as bands with a single voice, The Band is one example.)

The other weakness of the album can be found in some of the arrangements. Throughout the latter half of the sixties, Butterfield plays a significant role in the introduction of Rhythm & Blues artists, and their music, to the fresh ears in mainstream Rock, but by '71, his contributions are forgotten. So, when he records a mere duplication of Ray Charles' Drown in My Own Tears or Albert King's Oh Pretty Woman it comes off as trite - lazy behavior for a band of Butterfield's stature.

The other weakness of the album can be found in some of the arrangements. Throughout the latter half of the sixties, Butterfield plays a significant role in the introduction of Rhythm & Blues artists, and their music, to the fresh ears in mainstream Rock, but by '71, his contributions are forgotten. So, when he records a mere duplication of Ray Charles' Drown in My Own Tears or Albert King's Oh Pretty Woman it comes off as trite - lazy behavior for a band of Butterfield's stature.However, these are minor criticisms next to the album's strengths. Producer Paul Rothschild and Butterfield have added an powerful group of soulful background singers in Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Venetta Fields, and Oma Drake. Their addition to the band separates the album's music from all of the other horn bands which are springing up by the early seventies. The singers also allow for the addition of Gospel, Soul, and Funk influences into their music. Decades later, the album still sounds like a fresh blend of yeasty Americana music, with a soundscape reminiscent of a Phil Spector's, wall of sound.

Butterfield shows up as a much stronger songwriter on this album too. He has credits in over half of the nine compositions, all of them well crafted. Two of those compositions Night Child and Song for Lee should be recognized as the first Jazz/Rock instrumentals which feature a harmonica.

Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' even has the most pop oriented song ever recorded by any of the Butter bands. Butterfield and his wife Kathy, are credited to Blind Leading the Blind, a catchy Gospel flavoured shuffle. Unfortunately, it proves to be no match for hits by other top 70's horn bands: Chicago Transit Authority's new album 111 reaches # 2, Lighthouse's single One Fine Morning peaks at # 2, Blood Sweat and Tears' single Go Down Gamblin' #10, and even newcomers Edgar Winter's White Trash's first album is working its way up to # 70 on the album charts. The lack of promotion from Elektra is part of the reason Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' is struggling to hold on to #124 on the album charts.

It is easy to point to the lack of mainstream pop hits as the reason for the decline of the Butterfield Blues Band, but during the sixties, and early seventies, it isn't unusual for bands to have very successful careers with no major mainstream hits. In fact, fans of artists associated with the counter culture movement often consider the position as a badge of honor. However, that attitude is changing. By the early '70's Rock is becoming a huge industry feeding off massive outdoor festivals and album sales. Consequently, record labels, promoters, and artist managers are expecting bigger pay offs for their investments.

It is easy to point to the lack of mainstream pop hits as the reason for the decline of the Butterfield Blues Band, but during the sixties, and early seventies, it isn't unusual for bands to have very successful careers with no major mainstream hits. In fact, fans of artists associated with the counter culture movement often consider the position as a badge of honor. However, that attitude is changing. By the early '70's Rock is becoming a huge industry feeding off massive outdoor festivals and album sales. Consequently, record labels, promoters, and artist managers are expecting bigger pay offs for their investments.So, why does the Butterfield Blues Band end? There is no key breakdown in personnel as happens within the Beatles, or death of the voice of a band as is the case with Morrison or Joplin. There is none of that dynamic taking place in the Butter band. It seems that most plausible scenario is one which begins, and ends with one word, money.

Around 1970, Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman is spending most of his time away from his New York City management offices, and instead, focusing his energies on building his entertainment empire in Woodstock, New York. Some sources suggest that he makes this retreat because of the death of Janis Joplin, but this seems unlikely as a key reason. He is disappointed by the Blues singer's senseless departure, but he also collects on the 200K life insurance policy he purchases before her death. Grossman seems too calculating to succumb to such intense emotions. Regardless, he does retreat upstate, and consequently his business interests in the city suffer. This will prove to contribute to the end of Butterfield's band, but also push Butterfield's career in new, and more positive directions.

Around 1970, Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman is spending most of his time away from his New York City management offices, and instead, focusing his energies on building his entertainment empire in Woodstock, New York. Some sources suggest that he makes this retreat because of the death of Janis Joplin, but this seems unlikely as a key reason. He is disappointed by the Blues singer's senseless departure, but he also collects on the 200K life insurance policy he purchases before her death. Grossman seems too calculating to succumb to such intense emotions. Regardless, he does retreat upstate, and consequently his business interests in the city suffer. This will prove to contribute to the end of Butterfield's band, but also push Butterfield's career in new, and more positive directions. In addition, Butterfield's label Elektra Records has made a complete transition from recording acoustic folk in the early sixties to electric mainstream pop artists. The change is proving lucrative for them as they now employ some substantial revenue generators: the Doors, Bread, and Badfinger to name a few. These assets are definitely making more money for them than the Butterfield Blues Band. The band has not become a financial liability for them yet, but the label is beginning to neglect their investments in the band.

.jpg) So, the end of the Butterfield Blues Band seems to be best described as a product of business the dynamics between Grossman & Elektra. Butterfield is just an artist caught in the middle. During this period he is about to be faced with decisions he does not want to make. He just wants to carry on creating music, but whether he likes it or not Grossman presents him with this ultimatum:, disband your group, leave Elektra, and come with me or face extinction. Grossman is starting his own label, Bearsville Records, and negotiates a distribution deal with Warner. He wants Butterfield to be one of his first artists, and so secures him a $250,000 deal. (a large sum of money in '71)

So, the end of the Butterfield Blues Band seems to be best described as a product of business the dynamics between Grossman & Elektra. Butterfield is just an artist caught in the middle. During this period he is about to be faced with decisions he does not want to make. He just wants to carry on creating music, but whether he likes it or not Grossman presents him with this ultimatum:, disband your group, leave Elektra, and come with me or face extinction. Grossman is starting his own label, Bearsville Records, and negotiates a distribution deal with Warner. He wants Butterfield to be one of his first artists, and so secures him a $250,000 deal. (a large sum of money in '71)The dilemma for Butterfield is if he stays with a Elektra, he will probably lose Grossman as his manager, and his future with the label is not looking positive anyway. As Nick Gravenites describes the situation, Albert had made Paul a huge record deal with Warner Brothers, which was affiliated with Grossman’s Bearsville label, He told him, I’ll give the money to you, but I won't give it to (the other band members). If you take it - just you can keep it. If you split it with the band, they've got to pay off their debt to me. Paying their debt consisting of expenses typically covered by management would have wiped out the funds from Butterfield’s deal, .... Paul was begging pleading with him not to do that, says Gravenites. In the end, though, Paul took the money. If you are standing on the outside of this decision, the solution may appear simple, but for Butterfield it is about more than just money, there is security, attachment to Grossman, and loyalty to his band members, and family to consider.

In addition to all of the business issues facing him, Butterfield also has personal considerations too. He has been living in Woodstock for three years now, remarried, has a young son, Lee, a comfortable house with several acres on Highway 212, a couple of horses, two dogs, and many musician friends in the area. (the photos for the album cover are done in his backyard.) Most of his domestic stability is a result of his reputation as a musician, a bandleader, and seven years on the road. There must be times when he feels isolated, relieved, contented, and yet anxious about the potential of being unemployed with no band to call his own. The whole emotionally exhausting experience must leave him caught somewhere between smiling, and wishing for better days.

In addition to all of the business issues facing him, Butterfield also has personal considerations too. He has been living in Woodstock for three years now, remarried, has a young son, Lee, a comfortable house with several acres on Highway 212, a couple of horses, two dogs, and many musician friends in the area. (the photos for the album cover are done in his backyard.) Most of his domestic stability is a result of his reputation as a musician, a bandleader, and seven years on the road. There must be times when he feels isolated, relieved, contented, and yet anxious about the potential of being unemployed with no band to call his own. The whole emotionally exhausting experience must leave him caught somewhere between smiling, and wishing for better days.Every artist's career conforms to its own trajectory, the commonality is that they all rise from obscurity, peak, and begin a descent back into obscurity. For pop bands the process usually takes about five years, but blues bands, it's only two years. Most of the time it has nothing to do with the creative energy, or the quality of music, but rather situations which are out of their control. The trick is that once an artist reaches their peak, they need to drag out the decline as long as possible. The Rolling Stones have been coasting down for thirty years, and the Beatles even longer. In the case of the Butterfield Blues Band's career, it seems to peak with The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw, and then declines to reach its end with Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin'.

In '72, Elektra will release Golden Butter: The Best of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. It is testament to the financial impact the band has on Elektra Records; most of the double album is devoted to the first two albums, offers only minor recognition to everything else the Butter Band records, and only whispered lip service to the other contributions he makes to popular music in the 1960s. It peaks at #136 on the album charts. In addition, U.K. label Red Lightin' releases An Offer You Can't Refuse (see post #3) in 1972.

In '72, Elektra will release Golden Butter: The Best of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. It is testament to the financial impact the band has on Elektra Records; most of the double album is devoted to the first two albums, offers only minor recognition to everything else the Butter Band records, and only whispered lip service to the other contributions he makes to popular music in the 1960s. It peaks at #136 on the album charts. In addition, U.K. label Red Lightin' releases An Offer You Can't Refuse (see post #3) in 1972.The irony of the end of the Butterfield Blues Band is that for the remaining life of Paul Butterfield's career, he will be constantly measured by the what he accomplishes in his original Butterfield Blues Bands. The one relief for him in his the new phase of his career is that he will never have to answer interview questions requesting an explanation of why his music isn't blues. That question must have wiped the smile from his face a few times.

the Butterfield Blues Band : Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin'

1) Play On, 2) 1000 Ways, 3) Pretty Woman, 4) Little Piece of Dying, 5) Song For Lee, 6) Trainman, 7) Night Child, 8) Drown In My Own Tears, 9) Blind Leading The Blind.

Paul Butterfield: Vocal, harmonica, (piano on Blind Leading The Blind), Gene Dinwiddie: Tenor & soprano saxophone, flute, tambourine, (vocal on Drowned In My Own Tears), Rod Hicks: Bass, (vocal on 1000 Ways), Ralph Wash: Guitar, (vocal on Pretty Woman), Dennis Whitted: Drums, Bobby Hall:, Conga, bongos, Ted Harris:, Piano on Night Child, and Play On, George Davidson: - Drums on Night Child, and Play On, Trevor Lawrence: - Baritone saxophone, David Sanborn: Alto saxophone, Steve Madaio: Trumpet, Big Black: Congas.

Background Vocals: Clydie King, Merry Clayton, Venetta Fields, Oma Drake, Paul Butterfield, Rod Hicks, Ralph Wash, Gene Dinwiddie.

Producer: Paul Rothchild, Recording Engineers: Fritz Richmond, Bruce Botnick, Marc Harmon. Re-mixing Engineer: Fritz Richmond. Mixing: Todd Rundgren, Album Photography: Barry Feinstein.

No comments:

Post a Comment