Almost two decades after

white middle class Americans develop their infatuation with post-war blues, a new

generation of suburbanites are falling under the spell of another urban folk

music called Rap. Similar to blues, Rap boasts

vivid tales about the pursuit of unrestrained and gritty pleasures on the

lawless side of a big city.

There is another similarity

that Rap and in particular Gangsta Rap shares with urban blues, in

particular, 1960s white blues. It is the emphasis on a journeyman's profile as

a badge of respect, or as the Rappers

call it, Street Cred. The marketing departments of every record

label know of its importance, and go to great lengths to secure it for their

artists. Street Cred is seal of

approval that Paul Butterfield enjoys for the first ten years of his

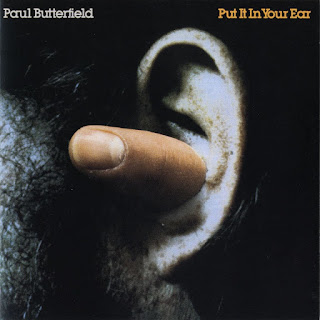

career, but after he releases his ninth album Put It In Your Ear in

February of 1976, seal of approval is starting to peel

away like the paint on a neglected ghetto window sill.

By the middle of the

seventies critics applaud him as the first white

bluesman to interpret blues

with an authentic conviction usually reserved for African-American counterparts. Part

of the reason is that he carries the prestigious credentials is that almost every

article written about him devotes about fifty percent to his past

accomplishments before any discussion of his current work is given mention.

By the middle of the

seventies critics applaud him as the first white

bluesman to interpret blues

with an authentic conviction usually reserved for African-American counterparts. Part

of the reason is that he carries the prestigious credentials is that almost every

article written about him devotes about fifty percent to his past

accomplishments before any discussion of his current work is given mention.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries, most of the accolades

critics shower on Butterfield are actually a product of talent and hard work not a fabrication of the press. He really does have the documentation to

prove his apprenticeship and journeyman's papers. In addition, his resume cites

years of grueling road tours, film and television performances, and innumerable

studio appearance that enhance his own catalogue of recordings. Street credentials aside, Butterfield also proves himself to be a pioneer in popular

music, an innovator, and a respected bandleader. He is the real deal. As journalist Albert Goldman notes in his

1968 essay on the bluesman, Butterfield has always had always true sense of

the real thing....

As an example of one of his many historical contributions to popular music, his band Better Days is part

of a select group of artists who pioneer the

new genre of roots music which will become known as Americana

Music. Part of the widespread appeal of his music as a skillful blend

of very hip, urban blues, folk, rock, and jazz, which strives to be anti-pop is still popular decades after release. As

one critic notes, His

blues collage is pasted together out of black New York jazz of the sixties,

blues Memphis soul of the late sixties and moire-screen orientalism from Frisco

'67.

However, in spite of any grand honors an artist's

receives, they are really only as good their last performance. Even though

every Butterfield project proves to

be yet another example of a clear artistic vision for a new music, that ability

seems to be fading by the time he records Put

It in Your Ear. It is here that his artistic acumen falters under the

weight of his gnawing drug addiction. If there is a point where his fans and

critics begin to question his street cred it is with this

album.

The most

recent stage of his artistic decline seems to begin in early '75 when hires the new Woodstock production company RCO to produce the new project. RCO (Our Company) is a business venture that music industry legend Henry

Glover, and his rock star friend, Levon

Helm concoct as their second

career. Their first production contract The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album puts

their company on the spotlight with a Grammy for Best

Ethnic or Traditional Recording. The prestigious award generates some industry

interest, enough to convince Butterfield to sign up as the company's second

client.

The most

recent stage of his artistic decline seems to begin in early '75 when hires the new Woodstock production company RCO to produce the new project. RCO (Our Company) is a business venture that music industry legend Henry

Glover, and his rock star friend, Levon

Helm concoct as their second

career. Their first production contract The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album puts

their company on the spotlight with a Grammy for Best

Ethnic or Traditional Recording. The prestigious award generates some industry

interest, enough to convince Butterfield to sign up as the company's second

client.

One of

the appeals of the project to Butterfield is that offers him an opportunity to

shed the weighty responsibilities of being a bandleader, leaving the heavy

lifting to the businessmen. However, this decision will prove to be a mistake because once he

submits to the seduction of RCO, he loses control of any vision he may bring to the

transaction.

It could

be his desire to break free of past projects, or his inflated ego, but Put It In your Ear is definitely

an error in judgement. While he considers Helm to be the best drummer he

has ever played with, he seems more enthralled with Glover's curriculum vitae, Henry's done a lot of

work over the years for people like Diana Washington, Ray Charles and Hank

Ballard. He's a black man in his 50s, and I've known him for about three years.

We met on some session in New York. He worked with me and Garth

Hudson and Levon Helm on that Muddy Waters album we did for Chess. However,

the two factors that Butterfield neglects to consider are that Glover's

past accomplishments are redundant to most in the mid-seventies rock scene, and

while Helm is ambitious, he also suffers from inexperience.

There is

another factor to consider in the failure of this project though. The communication

between an artist and his label is crucial for the ongoing success of both parties. In spite of what an artist wants to record, their label knows what will sell, and will often nix projects that look unprofitable. However, Albert Grossman's new label Bearsville Records is different from most other

labels. They maintain a hands off philosophy with both the

personal lives of their artists, and the projects they want to produce. It

seems like an unorthodox business model, but it proves very successful for most

of their stable of artists.

There is

another factor to consider in the failure of this project though. The communication

between an artist and his label is crucial for the ongoing success of both parties. In spite of what an artist wants to record, their label knows what will sell, and will often nix projects that look unprofitable. However, Albert Grossman's new label Bearsville Records is different from most other

labels. They maintain a hands off philosophy with both the

personal lives of their artists, and the projects they want to produce. It

seems like an unorthodox business model, but it proves very successful for most

of their stable of artists.

It could

be that the success Bearsville has with Paul

Butterfield's Better Days is a signal tot them that anything Butterfield touches

will reap financial rewards for the label. However, this time their laissez faire

attitude is will cost them revenue. The

recording of Put It In Your Ear is expensive by the standards of blues

singers of the day, Butterfield confides, We used 25

pieces (actually 48) on the

sessions and almost everything was done in one take. At $4000 (18k in 2016 dollars) a session you can't screw

around. We did the whole thing in three days in New York plus two three hour

session in L.A. These are

premium rates in the seventies, and so it is a surprising that no one at

Bearsville questions the project spending.

Part of

the cost of the album is the expensive use of some of the most skilled studio

musicians in the business. When you look at the lineup of talents, you can see that Butterfield is really

asserting his reputation as a artistic force in the industry. Among the supporting

forty-eight musicians are some of the industry's important luminaries: Chuck Rainy and James

Jamerson on bass, Garth Hudson, Eric Gale, and then there is

the flock of 11 string players, and bank of 12 horns. The magnitude of the project is not lost on Butterfield either, he boasts to one critic, Fred Carter, who's a great

Nashville guitarist and a terrific song writer, was on that one also. He wrote

one of the songs on the new record. Henry wrote two, Aaron Banks, who wrote

'Ain't that a lot of Love' write one, there's Hirth Martinez song, and one song

that was written by Bobby Charles and Robbie Robertson. There' also one of

mine. However, Put It In Your Ear should also be viewed as an example of

how albums often fail in spite of the quality of the individual components of

the project.

Part of

the cost of the album is the expensive use of some of the most skilled studio

musicians in the business. When you look at the lineup of talents, you can see that Butterfield is really

asserting his reputation as a artistic force in the industry. Among the supporting

forty-eight musicians are some of the industry's important luminaries: Chuck Rainy and James

Jamerson on bass, Garth Hudson, Eric Gale, and then there is

the flock of 11 string players, and bank of 12 horns. The magnitude of the project is not lost on Butterfield either, he boasts to one critic, Fred Carter, who's a great

Nashville guitarist and a terrific song writer, was on that one also. He wrote

one of the songs on the new record. Henry wrote two, Aaron Banks, who wrote

'Ain't that a lot of Love' write one, there's Hirth Martinez song, and one song

that was written by Bobby Charles and Robbie Robertson. There' also one of

mine. However, Put It In Your Ear should also be viewed as an example of

how albums often fail in spite of the quality of the individual components of

the project.

It only

takes one listen of the album to

understand that this is technically an excellent album. Even the euphemistic

album title Put It In Your Ear,

and the product packaging demonstrates clever marketing, but those incidentals don't

have much staying power with fans or critics, who mostly recoil when hearing it. One critic

erroneously says, ...his talent is undermined by flaccid

arrangements and atrocious material. Even

Rolling Stone's Kit Rachlis writes Even a career

predicated on experimentation, Paul Butterfield breaks a number of precedents

with Put It In Your

Ear. However, while most

critics focus on the songwriting and production, they neglect to address the

real issue of a mismatch of material with

artist persona.

There is

another more subtle reason for the failure of Put

It In Your Ear . There are

some historical trends developing in the mid-seventies which might contribute

to Butterfield's decision to record this album. Consider, he is respected as a trailblazer in history of popular music, but with this album he

becomes a follower of mainstream fads.

The historical

pattern in popular music tends to be that every decade gives birth to a new

generation of young people who feel disenfranchised from the offerings of the

mainstream, and so, seek out a new music. There are many examples of this

pattern, from Dixieland in the 20s, Be-bop in the 40s, Rock and Roll in the 50s, and then the melding of

Folk/Blues and Rock in the 60s. However, as a new music

gains popularity, the music industry sniffs out ways to capitalize on its

popularity. One thing they usually do is strip away any unique characteristics,

(i.e. country music) and then promote a pasteurized version to the mainstream

audiences. Finally, when the music becomes part of the mainstream market, the

original audience recoils from its redundancy, and so the cycle continues. Remember, it is

this dynamic which introduces The

Paul Butterfield Blues Band to

the world in the mid sixties.

So, how

does this pattern tie in with Paul

Butterfield's album Put It In Your Ear? Well, by 1975, genuine post-war blues has been marketed to mainstream audiences for a decade, and audience interest is stagnating. Butterfield, and many of his white Blues/Rock contemporaries have established audiences, enjoy the very envious

position of signing lucrative recording contracts, and participating in big

budget tours. As a reaction to this trend

a younger generation are starting to seek out a new music.

So, how

does this pattern tie in with Paul

Butterfield's album Put It In Your Ear? Well, by 1975, genuine post-war blues has been marketed to mainstream audiences for a decade, and audience interest is stagnating. Butterfield, and many of his white Blues/Rock contemporaries have established audiences, enjoy the very envious

position of signing lucrative recording contracts, and participating in big

budget tours. As a reaction to this trend

a younger generation are starting to seek out a new music.

Disco, is a loud, exciting, fresh music which employs, in-your-face vocals over a steady

four-on-the-floor beat, prominent syncopated electric bass lines, string

sections, horns, electric piano, and electronic synthesizers. It becomes so

popular that many of the more ambitious blues/rock acts like the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Rod Stewart, and Paul Butterfield will

attempt expand their market share by capitalizing on the popularity of the new pop

music. Many acts will have some success pandering to the disco craze,

but others will not, and Paul

Butterfield is one of them.

Herein

lies the main problem with Put

It In Your Ear, it should be a musical event, by a historically

significant artist, but it sounds like a feeble attempt at pandering to the disco

fad. Remember, Butterfield's public persona is of a

progressive blues singer, who composes and interprets gritty blues based music,

and then adventurously bridges genres of music, so his new album seems crassly

superficial. Listen to Day to

Day, Breadline, I Don't Want to Go with their very distinctive 70s social

commentary, but then notice how Butterfield's once

evocative harp solos seem to doze just at the surface of the mix.

Then

there is Fred Carter's saccharin based syrupy If I

Never Sing My Song, which sounds

more like an attempt to turn Butterfield into a lounge singer at a two star

motel bar on the outskirts of Las Vegas rather than that of the white boy

who masters Muddy Water's Just To Be With You at Smitty's

Corner. If there is a single song on the album that damages Butterfield's street cred as a blues singer, it this track.

It gets

worse. One of the highlights of Paul

Butterfield's Better Days two

albums is their interpretation of the Charles/Danko composition Small Town Talk. It is an

insightful social commentary on the incestuous, mostly melodramatic social

scene that Woodstock becomes by the mid-seventies. Now, compare it to what

sounds like Butterfield's attempt at

a sequel. Glover's Watch'em Tell a Lie, replete with a Barry White intro, and very unconvincing spoken

introduction by Butterfield, and an anonymous female stand in. Similar to so

many of the other songs on the album, they are so distant from the Paul Butterfield of the last ten years

that they sound contrived, and consequently pathetic.

It gets

worse. One of the highlights of Paul

Butterfield's Better Days two

albums is their interpretation of the Charles/Danko composition Small Town Talk. It is an

insightful social commentary on the incestuous, mostly melodramatic social

scene that Woodstock becomes by the mid-seventies. Now, compare it to what

sounds like Butterfield's attempt at

a sequel. Glover's Watch'em Tell a Lie, replete with a Barry White intro, and very unconvincing spoken

introduction by Butterfield, and an anonymous female stand in. Similar to so

many of the other songs on the album, they are so distant from the Paul Butterfield of the last ten years

that they sound contrived, and consequently pathetic.

Then

there is one of Butterfield's compositions The Flame. It too is another blatant

opportunity to capitalize on the disco fad. In case you are curious, he is

using the trendy 70s synthesizer invented by Alan Robert Pearlman called ARP. It is one of those instruments

that becomes so popular in the 70s that you can hear it in many of the pop

songs of the decade. (Edgar Winter uses

one on his hit instrumental Frankenstein)

When you listen to The Flame, and

compare it with an earlier Butterfield composition Song for Lee, it is difficult not to be struck how directionless The Flame is as a piece of music.

However,

the whole of Put It In Your Ear

is not a failure. There are three tracks that offer some redemption for Butterfield: You

Can Run But You Can’t Hide, The

Animal, and Ain't that a

lot of Love. These are examples of material which are better suited to

Butterfield persona, and can fit very neatly in any one of his concert setlists.

As a side note, You Can Run

But You Can't Hide is often

attributed to either Freddie King or

Luther Allison because both cover it

in the 70s, but it is in fact Butterfield/Glover composition. Royal Southern

Brotherhood, and Welsh singer Philip

Sayce will cover the tune in

the 2000s.

It is one

thing to record an album of new material, but quite another to promote the

project to your fans with a road tour. The live shows need to compliment the album, and Butterfield can't afford

to ever offer Put It In Your Ear to a live audience. The logistics of

mounting a tour with the weight of all the studio musicians will simply be too

costly. It's one of the reasons why major artists like Frank Sinatra or Celine

Dion hunker down in Las

Vegas.

It is one

thing to record an album of new material, but quite another to promote the

project to your fans with a road tour. The live shows need to compliment the album, and Butterfield can't afford

to ever offer Put It In Your Ear to a live audience. The logistics of

mounting a tour with the weight of all the studio musicians will simply be too

costly. It's one of the reasons why major artists like Frank Sinatra or Celine

Dion hunker down in Las

Vegas.

However, Butterfield is either deluded by his own wishful

thinking, or he is desperately overselling the album when he says, But everything we did in the studio

we can do on stage. I'm forming a new band, and we'll be doing a lot of the new

songs. I'm not precisely sure how many people are going to play, but I'll use

Chris Parker and Richard Bell (drums and keyboards), probably two guitars and

maybe a girl singer and one horn. My playing doesn't change much, though. The

musical concepts change but my playing is always the same. I think people still

crave that good old like music. Sure there la lot of theatrics around now, but

I think a lot of people really identify with straight happy shows. Man, when I

play I'm happy. It is a boast

that will never materialize.

However,

he does manage to form a modest road band, and then mount a sporadic tour; one

which will take him to areas on the south that only a decade earlier he swore

he would never play. His touring band is made up of out-of-work rock star sidemen Goldy McJohn keyboards), young upstart Rick Reed (bass), and fellow alcoholic Dallas Taylor (drums). They do appear at the July

1976 edition of the Montreux

Jazz Festival, and while it has yet to surface, there

is a video made for a television special, and apparently a live recording. I have

part of one recording from that tour Live

at the Pipeline Tavern in

Seattle Washington, July 29th 1976 where Butterfield demonstrates that his harp

playing is better than ever, but the set list is made up of blues standards, nothing from Put It In Your Ear.

However,

he does manage to form a modest road band, and then mount a sporadic tour; one

which will take him to areas on the south that only a decade earlier he swore

he would never play. His touring band is made up of out-of-work rock star sidemen Goldy McJohn keyboards), young upstart Rick Reed (bass), and fellow alcoholic Dallas Taylor (drums). They do appear at the July

1976 edition of the Montreux

Jazz Festival, and while it has yet to surface, there

is a video made for a television special, and apparently a live recording. I have

part of one recording from that tour Live

at the Pipeline Tavern in

Seattle Washington, July 29th 1976 where Butterfield demonstrates that his harp

playing is better than ever, but the set list is made up of blues standards, nothing from Put It In Your Ear.

The album

could be a product of Butterfield's frivolous artistic folly, or Bearsville's neglect,

but in the end, it never does capture the imagination of his fan base. Shortly

after its release Grossman hires Ian

Kimmet from Britain to run the day to day affairs of his studio operations and assigns the Butterfield account as his first file. During his first

meeting with Butterfield, Kimmet recalls I remember quite clearly the first

time I was with Paul, in a bar in Woodstock, and he was looking me right in the

eyes and asked, 'You didn't like my record with Henry Glover? Do you know who

Henry Glover is?' .....He said to me, 'Why don't my records sell over in

Europe?,' and I answered quite clearly that nobody was getting a buzz over

them. He laughed at my terminology. I told him that I thought he needed better

material, and I told him I thought the record just wasn't enough. He was

clearly amused by all of my comments.

While Butterfield might be smiling on the outside,

he seems to be aware of his loss of street

cred as critics are looking for answers to several questions about his

activities. He puts on a brave face, and defensively excuses his recent behavior,

I've really been taking it easy for the past year and a

half...... Well, I really needed some time to think things over, to work

on my life and my music. A lot of people take themselves too seriously. I try

not to, I live to laugh at myself, and that's good because it takes work to

stay open. But it's a necessity to stay open. A while ago I got to a point

where I knew I didn't have to play all the time, when I felt good about myself.

When you're 19 things are very intense, but when you're 34 , like I am, their

intense in another way. I've always tried to believe in my fellow man and

believe in myself.

Butterfield's career is no hurry to

recover after Put It In

Your Ear either. His

substance addictions are continuing to drain his financial resources, his wife

leaves him, he still doesn't want to tour, and he only has one album left in

his four album contract with Bearsville.

As mainstream audiences continue to lose interest with new blues artists Butterfield is

fortunate to still possess some important street

cred as draw to the shrinking venues he is forced to play.

The one

bright light will come when he appears with his friends and neighbors the Band at their farewell concert. In the film The Last Waltz he will be immortalized singing material more suited to his persona as a legendary bluesman. After the

Band decides to dissolve, Helm

will form his dream group called the RCO

All Stars, and Butterfield will be the group's first call

soloist. However, as both his personal and professional life is fraught with declining health and professional failures, the late seventies will continue to be a stark unforgiving period for the once great bluesman. During these years the only thing he seems to have left is

his street

cred .

Paul Butterfield Put

It In Your Ear Bearsville BR-6960 February 1976

Paul Butterfield - Vocal, harmonica, keyboards (ARP and Synthesizer)

Almost two decades after

white middle class Americans develop their infatuation with post-war blues, a new

generation of suburbanites are falling under the spell of another urban folk

music called Rap. Similar to blues, Rap boasts

vivid tales about the pursuit of unrestrained and gritty pleasures on the

lawless side of a big city.

There is another similarity

that Rap and in particular Gangsta Rap shares with urban blues, in

particular, 1960s white blues. It is the emphasis on a journeyman's profile as

a badge of respect, or as the Rappers

call it, Street Cred. The marketing departments of every record

label know of its importance, and go to great lengths to secure it for their

artists. Street Cred is seal of

approval that Paul Butterfield enjoys for the first ten years of his

career, but after he releases his ninth album Put It In Your Ear in

February of 1976, seal of approval is starting to peel

away like the paint on a neglected ghetto window sill.

By the middle of the

seventies critics applaud him as the first white

bluesman to interpret blues

with an authentic conviction usually reserved for African-American counterparts. Part

of the reason is that he carries the prestigious credentials is that almost every

article written about him devotes about fifty percent to his past

accomplishments before any discussion of his current work is given mention.

By the middle of the

seventies critics applaud him as the first white

bluesman to interpret blues

with an authentic conviction usually reserved for African-American counterparts. Part

of the reason is that he carries the prestigious credentials is that almost every

article written about him devotes about fifty percent to his past

accomplishments before any discussion of his current work is given mention.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries, most of the accolades

critics shower on Butterfield are actually a product of talent and hard work not a fabrication of the press. He really does have the documentation to

prove his apprenticeship and journeyman's papers. In addition, his resume cites

years of grueling road tours, film and television performances, and innumerable

studio appearance that enhance his own catalogue of recordings. Street credentials aside, Butterfield also proves himself to be a pioneer in popular

music, an innovator, and a respected bandleader. He is the real deal. As journalist Albert Goldman notes in his

1968 essay on the bluesman, Butterfield has always had always true sense of

the real thing....

As an example of one of his many historical contributions to popular music, his band Better Days is part of a select group of artists who pioneer the new genre of roots music which will become known as Americana Music. Part of the widespread appeal of his music as a skillful blend of very hip, urban blues, folk, rock, and jazz, which strives to be anti-pop is still popular decades after release. As one critic notes, His blues collage is pasted together out of black New York jazz of the sixties, blues Memphis soul of the late sixties and moire-screen orientalism from Frisco '67.

However, in spite of any grand honors an artist's

receives, they are really only as good their last performance. Even though

every Butterfield project proves to

be yet another example of a clear artistic vision for a new music, that ability

seems to be fading by the time he records Put

It in Your Ear. It is here that his artistic acumen falters under the

weight of his gnawing drug addiction. If there is a point where his fans and

critics begin to question his street cred it is with this

album.

The most

recent stage of his artistic decline seems to begin in early '75 when hires the new Woodstock production company RCO to produce the new project. RCO (Our Company) is a business venture that music industry legend Henry

Glover, and his rock star friend, Levon

Helm concoct as their second

career. Their first production contract The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album puts

their company on the spotlight with a Grammy for Best

Ethnic or Traditional Recording. The prestigious award generates some industry

interest, enough to convince Butterfield to sign up as the company's second

client.

The most

recent stage of his artistic decline seems to begin in early '75 when hires the new Woodstock production company RCO to produce the new project. RCO (Our Company) is a business venture that music industry legend Henry

Glover, and his rock star friend, Levon

Helm concoct as their second

career. Their first production contract The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album puts

their company on the spotlight with a Grammy for Best

Ethnic or Traditional Recording. The prestigious award generates some industry

interest, enough to convince Butterfield to sign up as the company's second

client.

One of

the appeals of the project to Butterfield is that offers him an opportunity to

shed the weighty responsibilities of being a bandleader, leaving the heavy

lifting to the businessmen. However, this decision will prove to be a mistake because once he

submits to the seduction of RCO, he loses control of any vision he may bring to the

transaction.

It could

be his desire to break free of past projects, or his inflated ego, but Put It In your Ear is definitely

an error in judgement. While he considers Helm to be the best drummer he

has ever played with, he seems more enthralled with Glover's curriculum vitae, Henry's done a lot of

work over the years for people like Diana Washington, Ray Charles and Hank

Ballard. He's a black man in his 50s, and I've known him for about three years.

We met on some session in New York. He worked with me and Garth

Hudson and Levon Helm on that Muddy Waters album we did for Chess. However,

the two factors that Butterfield neglects to consider are that Glover's

past accomplishments are redundant to most in the mid-seventies rock scene, and

while Helm is ambitious, he also suffers from inexperience.

There is

another factor to consider in the failure of this project though. The communication

between an artist and his label is crucial for the ongoing success of both parties. In spite of what an artist wants to record, their label knows what will sell, and will often nix projects that look unprofitable. However, Albert Grossman's new label Bearsville Records is different from most other

labels. They maintain a hands off philosophy with both the

personal lives of their artists, and the projects they want to produce. It

seems like an unorthodox business model, but it proves very successful for most

of their stable of artists.

There is

another factor to consider in the failure of this project though. The communication

between an artist and his label is crucial for the ongoing success of both parties. In spite of what an artist wants to record, their label knows what will sell, and will often nix projects that look unprofitable. However, Albert Grossman's new label Bearsville Records is different from most other

labels. They maintain a hands off philosophy with both the

personal lives of their artists, and the projects they want to produce. It

seems like an unorthodox business model, but it proves very successful for most

of their stable of artists.

It could

be that the success Bearsville has with Paul

Butterfield's Better Days is a signal tot them that anything Butterfield touches

will reap financial rewards for the label. However, this time their laissez faire

attitude is will cost them revenue. The

recording of Put It In Your Ear is expensive by the standards of blues

singers of the day, Butterfield confides, We used 25

pieces (actually 48) on the

sessions and almost everything was done in one take. At $4000 (18k in 2016 dollars) a session you can't screw

around. We did the whole thing in three days in New York plus two three hour

session in L.A. These are

premium rates in the seventies, and so it is a surprising that no one at

Bearsville questions the project spending.

Part of

the cost of the album is the expensive use of some of the most skilled studio

musicians in the business. When you look at the lineup of talents, you can see that Butterfield is really

asserting his reputation as a artistic force in the industry. Among the supporting

forty-eight musicians are some of the industry's important luminaries: Chuck Rainy and James

Jamerson on bass, Garth Hudson, Eric Gale, and then there is

the flock of 11 string players, and bank of 12 horns. The magnitude of the project is not lost on Butterfield either, he boasts to one critic, Fred Carter, who's a great

Nashville guitarist and a terrific song writer, was on that one also. He wrote

one of the songs on the new record. Henry wrote two, Aaron Banks, who wrote

'Ain't that a lot of Love' write one, there's Hirth Martinez song, and one song

that was written by Bobby Charles and Robbie Robertson. There' also one of

mine. However, Put It In Your Ear should also be viewed as an example of

how albums often fail in spite of the quality of the individual components of

the project.

Part of

the cost of the album is the expensive use of some of the most skilled studio

musicians in the business. When you look at the lineup of talents, you can see that Butterfield is really

asserting his reputation as a artistic force in the industry. Among the supporting

forty-eight musicians are some of the industry's important luminaries: Chuck Rainy and James

Jamerson on bass, Garth Hudson, Eric Gale, and then there is

the flock of 11 string players, and bank of 12 horns. The magnitude of the project is not lost on Butterfield either, he boasts to one critic, Fred Carter, who's a great

Nashville guitarist and a terrific song writer, was on that one also. He wrote

one of the songs on the new record. Henry wrote two, Aaron Banks, who wrote

'Ain't that a lot of Love' write one, there's Hirth Martinez song, and one song

that was written by Bobby Charles and Robbie Robertson. There' also one of

mine. However, Put It In Your Ear should also be viewed as an example of

how albums often fail in spite of the quality of the individual components of

the project.

It only

takes one listen of the album to

understand that this is technically an excellent album. Even the euphemistic

album title Put It In Your Ear,

and the product packaging demonstrates clever marketing, but those incidentals don't

have much staying power with fans or critics, who mostly recoil when hearing it. One critic

erroneously says, ...his talent is undermined by flaccid

arrangements and atrocious material. Even

Rolling Stone's Kit Rachlis writes Even a career

predicated on experimentation, Paul Butterfield breaks a number of precedents

with Put It In Your

Ear. However, while most

critics focus on the songwriting and production, they neglect to address the

real issue of a mismatch of material with

artist persona.

There is

another more subtle reason for the failure of Put

It In Your Ear . There are

some historical trends developing in the mid-seventies which might contribute

to Butterfield's decision to record this album. Consider, he is respected as a trailblazer in history of popular music, but with this album he

becomes a follower of mainstream fads.

The historical

pattern in popular music tends to be that every decade gives birth to a new

generation of young people who feel disenfranchised from the offerings of the

mainstream, and so, seek out a new music. There are many examples of this

pattern, from Dixieland in the 20s, Be-bop in the 40s, Rock and Roll in the 50s, and then the melding of

Folk/Blues and Rock in the 60s. However, as a new music

gains popularity, the music industry sniffs out ways to capitalize on its

popularity. One thing they usually do is strip away any unique characteristics,

(i.e. country music) and then promote a pasteurized version to the mainstream

audiences. Finally, when the music becomes part of the mainstream market, the

original audience recoils from its redundancy, and so the cycle continues. Remember, it is

this dynamic which introduces The

Paul Butterfield Blues Band to

the world in the mid sixties.

So, how

does this pattern tie in with Paul

Butterfield's album Put It In Your Ear? Well, by 1975, genuine post-war blues has been marketed to mainstream audiences for a decade, and audience interest is stagnating. Butterfield, and many of his white Blues/Rock contemporaries have established audiences, enjoy the very envious

position of signing lucrative recording contracts, and participating in big

budget tours. As a reaction to this trend

a younger generation are starting to seek out a new music.

So, how

does this pattern tie in with Paul

Butterfield's album Put It In Your Ear? Well, by 1975, genuine post-war blues has been marketed to mainstream audiences for a decade, and audience interest is stagnating. Butterfield, and many of his white Blues/Rock contemporaries have established audiences, enjoy the very envious

position of signing lucrative recording contracts, and participating in big

budget tours. As a reaction to this trend

a younger generation are starting to seek out a new music.

Disco, is a loud, exciting, fresh music which employs, in-your-face vocals over a steady

four-on-the-floor beat, prominent syncopated electric bass lines, string

sections, horns, electric piano, and electronic synthesizers. It becomes so

popular that many of the more ambitious blues/rock acts like the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Rod Stewart, and Paul Butterfield will

attempt expand their market share by capitalizing on the popularity of the new pop

music. Many acts will have some success pandering to the disco craze,

but others will not, and Paul

Butterfield is one of them.

Herein

lies the main problem with Put

It In Your Ear, it should be a musical event, by a historically

significant artist, but it sounds like a feeble attempt at pandering to the disco

fad. Remember, Butterfield's public persona is of a

progressive blues singer, who composes and interprets gritty blues based music,

and then adventurously bridges genres of music, so his new album seems crassly

superficial. Listen to Day to

Day, Breadline, I Don't Want to Go with their very distinctive 70s social

commentary, but then notice how Butterfield's once

evocative harp solos seem to doze just at the surface of the mix.

Then

there is Fred Carter's saccharin based syrupy If I

Never Sing My Song, which sounds

more like an attempt to turn Butterfield into a lounge singer at a two star

motel bar on the outskirts of Las Vegas rather than that of the white boy

who masters Muddy Water's Just To Be With You at Smitty's

Corner. If there is a single song on the album that damages Butterfield's street cred as a blues singer, it this track.

It gets

worse. One of the highlights of Paul

Butterfield's Better Days two

albums is their interpretation of the Charles/Danko composition Small Town Talk. It is an

insightful social commentary on the incestuous, mostly melodramatic social

scene that Woodstock becomes by the mid-seventies. Now, compare it to what

sounds like Butterfield's attempt at

a sequel. Glover's Watch'em Tell a Lie, replete with a Barry White intro, and very unconvincing spoken

introduction by Butterfield, and an anonymous female stand in. Similar to so

many of the other songs on the album, they are so distant from the Paul Butterfield of the last ten years

that they sound contrived, and consequently pathetic.

It gets

worse. One of the highlights of Paul

Butterfield's Better Days two

albums is their interpretation of the Charles/Danko composition Small Town Talk. It is an

insightful social commentary on the incestuous, mostly melodramatic social

scene that Woodstock becomes by the mid-seventies. Now, compare it to what

sounds like Butterfield's attempt at

a sequel. Glover's Watch'em Tell a Lie, replete with a Barry White intro, and very unconvincing spoken

introduction by Butterfield, and an anonymous female stand in. Similar to so

many of the other songs on the album, they are so distant from the Paul Butterfield of the last ten years

that they sound contrived, and consequently pathetic.

Then

there is one of Butterfield's compositions The Flame. It too is another blatant

opportunity to capitalize on the disco fad. In case you are curious, he is

using the trendy 70s synthesizer invented by Alan Robert Pearlman called ARP. It is one of those instruments

that becomes so popular in the 70s that you can hear it in many of the pop

songs of the decade. (Edgar Winter uses

one on his hit instrumental Frankenstein)

When you listen to The Flame, and

compare it with an earlier Butterfield composition Song for Lee, it is difficult not to be struck how directionless The Flame is as a piece of music.

However,

the whole of Put It In Your Ear

is not a failure. There are three tracks that offer some redemption for Butterfield: You

Can Run But You Can’t Hide, The

Animal, and Ain't that a

lot of Love. These are examples of material which are better suited to

Butterfield persona, and can fit very neatly in any one of his concert setlists.

As a side note, You Can Run

But You Can't Hide is often

attributed to either Freddie King or

Luther Allison because both cover it

in the 70s, but it is in fact Butterfield/Glover composition. Royal Southern

Brotherhood, and Welsh singer Philip

Sayce will cover the tune in

the 2000s.

It is one

thing to record an album of new material, but quite another to promote the

project to your fans with a road tour. The live shows need to compliment the album, and Butterfield can't afford

to ever offer Put It In Your Ear to a live audience. The logistics of

mounting a tour with the weight of all the studio musicians will simply be too

costly. It's one of the reasons why major artists like Frank Sinatra or Celine

Dion hunker down in Las

Vegas.

It is one

thing to record an album of new material, but quite another to promote the

project to your fans with a road tour. The live shows need to compliment the album, and Butterfield can't afford

to ever offer Put It In Your Ear to a live audience. The logistics of

mounting a tour with the weight of all the studio musicians will simply be too

costly. It's one of the reasons why major artists like Frank Sinatra or Celine

Dion hunker down in Las

Vegas.

However, Butterfield is either deluded by his own wishful

thinking, or he is desperately overselling the album when he says, But everything we did in the studio

we can do on stage. I'm forming a new band, and we'll be doing a lot of the new

songs. I'm not precisely sure how many people are going to play, but I'll use

Chris Parker and Richard Bell (drums and keyboards), probably two guitars and

maybe a girl singer and one horn. My playing doesn't change much, though. The

musical concepts change but my playing is always the same. I think people still

crave that good old like music. Sure there la lot of theatrics around now, but

I think a lot of people really identify with straight happy shows. Man, when I

play I'm happy. It is a boast

that will never materialize.

However,

he does manage to form a modest road band, and then mount a sporadic tour; one

which will take him to areas on the south that only a decade earlier he swore

he would never play. His touring band is made up of out-of-work rock star sidemen Goldy McJohn keyboards), young upstart Rick Reed (bass), and fellow alcoholic Dallas Taylor (drums). They do appear at the July

1976 edition of the Montreux

Jazz Festival, and while it has yet to surface, there

is a video made for a television special, and apparently a live recording. I have

part of one recording from that tour Live

at the Pipeline Tavern in

Seattle Washington, July 29th 1976 where Butterfield demonstrates that his harp

playing is better than ever, but the set list is made up of blues standards, nothing from Put It In Your Ear.

However,

he does manage to form a modest road band, and then mount a sporadic tour; one

which will take him to areas on the south that only a decade earlier he swore

he would never play. His touring band is made up of out-of-work rock star sidemen Goldy McJohn keyboards), young upstart Rick Reed (bass), and fellow alcoholic Dallas Taylor (drums). They do appear at the July

1976 edition of the Montreux

Jazz Festival, and while it has yet to surface, there

is a video made for a television special, and apparently a live recording. I have

part of one recording from that tour Live

at the Pipeline Tavern in

Seattle Washington, July 29th 1976 where Butterfield demonstrates that his harp

playing is better than ever, but the set list is made up of blues standards, nothing from Put It In Your Ear.

The album

could be a product of Butterfield's frivolous artistic folly, or Bearsville's neglect,

but in the end, it never does capture the imagination of his fan base. Shortly

after its release Grossman hires Ian

Kimmet from Britain to run the day to day affairs of his studio operations and assigns the Butterfield account as his first file. During his first

meeting with Butterfield, Kimmet recalls I remember quite clearly the first

time I was with Paul, in a bar in Woodstock, and he was looking me right in the

eyes and asked, 'You didn't like my record with Henry Glover? Do you know who

Henry Glover is?' .....He said to me, 'Why don't my records sell over in

Europe?,' and I answered quite clearly that nobody was getting a buzz over

them. He laughed at my terminology. I told him that I thought he needed better

material, and I told him I thought the record just wasn't enough. He was

clearly amused by all of my comments.

While Butterfield might be smiling on the outside, he seems to be aware of his loss of street cred as critics are looking for answers to several questions about his activities. He puts on a brave face, and defensively excuses his recent behavior, I've really been taking it easy for the past year and a half...... Well, I really needed some time to think things over, to work on my life and my music. A lot of people take themselves too seriously. I try not to, I live to laugh at myself, and that's good because it takes work to stay open. But it's a necessity to stay open. A while ago I got to a point where I knew I didn't have to play all the time, when I felt good about myself. When you're 19 things are very intense, but when you're 34 , like I am, their intense in another way. I've always tried to believe in my fellow man and believe in myself.

You

see, the time I've spending hasn't been wasted. I've been listening to Pablo Casals. I've been sitting

in with Taj or Muddy or doing a little session work for friends like Happy and

Artie Traum. It's more fun, and it's better than getting paid a lot to do

sessions in New York. I've been writing on piano, playing more piano. And the

record company's been great; I've always had a lot of faith in Albert Grossman and Mo Ostin. I'm

going to be playing music all my life, just like Casals. I'm in no hurry.

Butterfield's career is no hurry to recover after Put It In Your Ear either. His substance addictions are continuing to drain his financial resources, his wife leaves him, he still doesn't want to tour, and he only has one album left in his four album contract with Bearsville. As mainstream audiences continue to lose interest with new blues artists Butterfield is fortunate to still possess some important street cred as draw to the shrinking venues he is forced to play.

The one

bright light will come when he appears with his friends and neighbors the Band at their farewell concert. In the film The Last Waltz he will be immortalized singing material more suited to his persona as a legendary bluesman. After the

Band decides to dissolve, Helm

will form his dream group called the RCO

All Stars, and Butterfield will be the group's first call

soloist. However, as both his personal and professional life is fraught with declining health and professional failures, the late seventies will continue to be a stark unforgiving period for the once great bluesman. During these years the only thing he seems to have left is

his street

cred .

Paul Butterfield Put

It In Your Ear Bearsville BR-6960 February 1976

You Can Run But You Can’t Hide, The

Flame, (If I Never Sing)

My Song, Day To Day, Ain’t That A Lot Of Love, The Breadline, The Animal, I Don’t Wanna Go, Here I Go Again, Watch’em Tell A Lie.

Paul Butterfield - Vocal, harmonica, keyboards (ARP and Synthesizer)

Strings: Sidney Sharp, Richard Kaufman, Karen Jones, Bernard Kundell

, Jack Pepper, Paul Shure,

Meyer Bello, Norman Forest, Jess

Ehrlich, Raphael Krammer, Christine Ermacoff

Woodwinds: Frank West, alto, Seldon Powell, tenor, babe Clark,

Baritone, Mel Tax, baritone ,

Jerome Richard, alto, Clifford

Shank, alto, Wilbur Schwartz, Gene Cipriano, David Sanborn, alto/soprano

Keyboards: Henry Glover, Garth Hudson, Richard Bell.

Brass: Lloyd Michels, trumpet, Irving Markowitz, trumpet, Al

DeRisi, trumpet Sonny Russo - Trombone

Reeds: Garth Hudson

Bass Sax: Howard Johnson

Electric bass: Chuck Rainy, Tim Drummond , James Jamerson, Gordon Edwards.

Guitars: Fred Carter Jr., Ben Keith, Eric Gale, John Holbrook, Nick

Jameson

Background Vocals: Gail Kanter, Chris Parker, Bernard Purdie, Steven Kroon

Drums and Percussion: Levon Helm, Erin Dickens, Ann Sutton, Evangeline

Carmichael, Lorna Willard, Julia Tillman, Andrea Willis.

Conductor/Arranger/Producer: Henry Glover,

Recording Engineers, Angel Balastier/TTG Studios (L. A., Cal.), Ed

Anderson/Shangrila Studios, (Malibu,Cal.), John Holbrook /Bearsville

Studios, (N.Y.), Tom Mark, Assistant Engineer, Bearsville, Mixed at Bearsville Studios,

Mastering Engineer: Mark Harmon,

Contractors: Mel Tax, George Berg,

Photography: Barry Feinstein,

Cover Design: Milton Glaser.