It is a

testament to an entrepreneur's talent when he no longer needs to seek out

customers because they are coming to him. This is the enviable position Albert

Grossman achieves during his career as the manager of several very successful

artists. His greatest strengths are the ability to sense artistic talent, and

then sell it. Many businessmen of his stature might choose to stay in the city

to show off symbols of their success, but he decides to move to rural New York

instead. It is here that he settles in the hamlet Bearsville, and begins

building a comparatively modest, yet impressive empire.

It is a

testament to an entrepreneur's talent when he no longer needs to seek out

customers because they are coming to him. This is the enviable position Albert

Grossman achieves during his career as the manager of several very successful

artists. His greatest strengths are the ability to sense artistic talent, and

then sell it. Many businessmen of his stature might choose to stay in the city

to show off symbols of their success, but he decides to move to rural New York

instead. It is here that he settles in the hamlet Bearsville, and begins

building a comparatively modest, yet impressive empire. Similar to Chess Records in Chicago, or Motown in Detroit, Grossman

designs his Bearsville Records empire to be a one stop shop for the 1970s music industry. It is replete

with temporary housing for his growing collection of employees, restaurants, a

recording studio, a support staff who skillfully attend to every need of his

growing stable of artists, and a head office for publishing. All of this points a man with a well developed

business acumen fueled with raw ambition. If he were less sophisticated, he might

hang a shingle outside his office that says, It you aren't growing, you're dying.

Similar to Chess Records in Chicago, or Motown in Detroit, Grossman

designs his Bearsville Records empire to be a one stop shop for the 1970s music industry. It is replete

with temporary housing for his growing collection of employees, restaurants, a

recording studio, a support staff who skillfully attend to every need of his

growing stable of artists, and a head office for publishing. All of this points a man with a well developed

business acumen fueled with raw ambition. If he were less sophisticated, he might

hang a shingle outside his office that says, It you aren't growing, you're dying. More specifically, his most obvious strength is boardroom

negotiating, but then there is his often overlooked talent of refraining from

micromanaging the careers of his artists. The unwritten bargain he has seems to

have with his artists is they are free to create music and he sells it. It is a

powerful combination, but it is also his greatest weakness. Of all the careers

he manages, Paul Butterfield's is a good example of everything that is both

good and bad about Albert Grossman's management style.

More specifically, his most obvious strength is boardroom

negotiating, but then there is his often overlooked talent of refraining from

micromanaging the careers of his artists. The unwritten bargain he has seems to

have with his artists is they are free to create music and he sells it. It is a

powerful combination, but it is also his greatest weakness. Of all the careers

he manages, Paul Butterfield's is a good example of everything that is both

good and bad about Albert Grossman's management style.

Remember, in 1965 he agrees to manager Butterfield's career

because he hears something visceral in the twenty three year olds brand of blues. Then,

in spite of the fact that Butterfield never becomes a comparatively strong commercial

success, he remains loyal to him, always treating him as an artist of remarkable

distinction. The fact is Paul Butterfield probably would never have sustained success if it were not for Albert Grossman. As Danny Goldberg

remembers, On the few occasions I saw him with Butterfield, Albert treated him with the greatest respect,

as someone who, regardless of whether he was making money from him or

not, was to be regarded as a major figure. However, their relationship must come under

intense questioning between 1975 and 1980, as Butterfield stops living up to

his end of the manager/artist bargain.

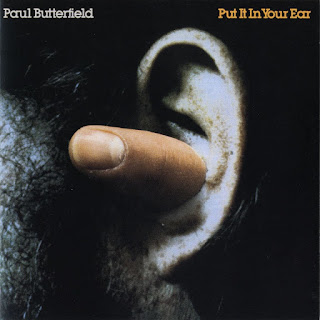

Butterfield's downward spiral seems to begin during the collapse of his second band Better Days. It is here that the young blues man begins to fall prey to his own demons. The solace he seeks through self medication with alcohol and street narcotics strips away most of his self confidence, and then slowly chips away at both his personal and professional life. His first solo project, Put It In Your Ear, shows fans what happens when one of the century's greatest bandleaders abandons his role to outsiders. After that failure, the only two projects that seem to keep his career floating are his impassioned performance at The Last Waltz, and then his brief, yet high profile position in Levon Helm's RCO All stars.

Then there is the failed attempt to resurrect his solo career with an appearance in September of '78, on

When

Butterfield returns stateside, he forms the Danko/Butterfield Band with friend

and fellow addict Rick Danko. They turn in some adequate shows but mostly, the short

barroom tours are a manipulation of the system to support their alcohol and

narcotic fueled lifestyle. It isn't long before rumors and eye witness accounts

of personality conflicts cause their performances to become unreliable. At one

gig, Danko plays only harmonica and Butterfield strums guitar, enraging the fans.

Eventually, every show becomes a potential powder keg of unpleasant surprises

for promoters, bar owners and fans. In the tightly knit music industry the two

former rock stars become known as the dangerous

duo.

It is this pattern of self-destruction that Butterfield tries to address when he confesses to Rolling Stone, I

These situations often prompt questions from

outsiders about the behavior of the bystanders who seem to simply watch catastrophe

unfold, so it is fair to wonder about Grossman's role during these years. It is possible that he is demonstrating a blind

loyalty, or looking for opportunities for a final payday. After all, it is

common knowledge that he does purchase a life insurance policy on Janis Joplin

shortly before she dies of a drug overdose. Maybe he was plotting ways to posthumously

capitalize on Butterfield's decline too-

we will never know.

However,

in Grossman's defense, Danny Goldberg

remembers, Albert Grossman stayed loyal. He really loved Paul,

and it broke his heart to see him fall apart the way he did. But Albert never

presumed to tell people how to live their lives. His philosophy was self-reliance. It is easy, to smugly look back at the

seventies, and wonder why the common error of bystanders to addiction catastrophes justify

their lack of intervention by professing loyalty, but the 70s is a different time. It seems that in

his own way, Grossman thinks the best remedy for Butterfield decline is to

encourage him to get back in the studio, and solve his problems through hard

work.

Contrary to Butterfield's career prognosis, Grossman's career

is still on a steady ascent. In the late seventies he is expanding his business

into new markets. Similar to Woodstock, the music scene in Memphis is also a

melting pot of great American music, only with a richer history that easily dates

back into the 19th century. The success of postwar labels like Sun, Stax, and

Hi are a testament to the vibrancy of the Memphis scene, but as the industry

fragments to other urban centres during the seventies, the Memphis labels become

vulnerable to corporate takeover.

It is during this period of decline that Grossman negotiates a deal with Willie Mitchell, and his label Hi Records. The agreement comes with the option to employ the talents of the famed singer, songwriter, arranger, producer, and businessman, and in the process help the Bearsville artists. Mitchell has an impressive production resume that includes luminaries such as Ann Peeples, and of course his star achievement, Al Green, so the transaction is a coup for Grossman. While the deal to expand into Memphis does serve several Bearsville's artists well, for Butterfield it spells disaster.

One of Mitchell's first Bearsville projects is with Butterfield's girlfriend Elizabeth Barraclough, who in 1979, records her second album Hi with Mitchell in Memphis. She is happy enough with the results of the project that she returns to Woodstock, and suggests to Butterfield that he and Mitchell might be a good fit. It has been five years since he has released any product, so he goes to Memphis with Barraclough, and according to Joe Perry, ...the Hodges brothers and Memphis horns would come around, and Paul knew of them. He fit right in with these guys. The Butterfield/Mitchell team should be a winning combination, but in spite of Mitchell's pedigree, the project will become yet another Butterfield disappointment.

Butterfield's relentless abuse with alcohol, various narcotics, combined with poor dietary habits take a toll on his body. In 1979 he develops an inflammation in his lower intestine called diverticulitis, which he does not address properly, and it develops into a more serious infection. The untreated inflammation causes a perforation of his intestine, which then allows puss and waste to enter the abdominal cavity. This damages the membrane which protects the internal organs known as the peritoneum, creating the condition known as peritonitis.

If his condition sounds dire, that's because it is.

Peritonitis is painful, and if not addressed quickly, will lead to certain

death. While in the Memphis studio, he collapses, and is rushed to the

hospital. He later will reflect that at the time, he thinks the pain is the

result of too much barbeque, but he is running out of that kind of good

fortune. Once a doctor diagnoses his peritonitis, he is hospitalized undergoes immediate surgery

where his colon is severed, and a colostomy bag connected, allowing the damaged

intestine area to heal. Then, the recovery advice by the doctors is that he remain

stationary, discontinue his abusive lifestyle, and alter his diet, but these sound

instructions are lost on someone armed with Butterfield's almost childish sense

of invincibility. It will not be long before a returns his old lifestyle.

A couple of years later he will confide in Don Snowdon of the L.A. Times, To

make a long story short, my

intestines burst...... I ended up having four

operations and you don't realize what it takes out of you, energy wise.,

he said, You think you can come right back , so I went back to work and

herniated the scar tissue in my stomach. I had three hernias from playing

the harmonica, so it was a vicious circle. Sure it occurred to me that might

not be able to play anymore, but I got that Irish ornery thing going and said,

I'm going to make it through this and I did with a lot of help from God. I came

through the wars there. Most rational

people will interpret these events as a dire warning from the body to the mind that

it is time for a lifestyle change, but just because people have the ability to

reason does not preclude that they use that ability. In spite of the health tragedy, the album is completed, and Bearville releases in January of 1981. It will prove to be a tough sell to fans of the once great blues man though. This writer can't help but wonder if at some point, the marketing department at Bearsville is at a loss for what to do with the album. Then in a desperate attempt to put a positive spin on it, conjure up the idea of masking its obvious weakness by comparing it to his ground breaking album East West by calling it North South. It is a nice try, but no one is fooled by the marketing shell game.

Firstly, the album has none of the gutsy boldness of East

West, or as one critic laments, Butterfield's 1980 album North-South

was neither bold or brash, just sterile and irrelevant. Only the slow closer

Baby Blue sounded like authentic Butterfield. Then there are other critics who dwell on its use

of strings, synthesizers, and pale funk arrangements, or use words

like fluff to describe the contents of North

South.

In an

effort to bring some context to the next criticism, it might be useful for

readers who are not familiar with 70s pop to take this short digression.

By 1981, the dance music trend known Disco

has run its course in U.S.. Part of the reason for its demise is because of a

nationally run campaign by radio stations, and trade magazines which often pokes

fun at the pop music as being too artificial.

It isn't long before kids are wearing t-shirts emblazoned with loud insult such

as Disco Sucks. So, by 1980, the word

Disco is a word millions use to insult,

not compliment, an artist's music. This relates to North South because there are critics who hurl the ultimate

insult at it. They take it one step further than just calling it Disco pushing it to next level calling it Bad Disco. For an artist

of Butterfield's caliber, such criticisms

must be devastating. Histrionics aside, North South is technically

excellent, and actually boasts some great grooves like Get Some Fun Out of Life.

There are not many positive reviews of North South,

and some critics seem more disappointed with the audacity of Butterfield's willingness to

deviate so far from his established persona as a blues man of great distinction.

The final nail in the coffin for his new

album is when David Fricke pens this one star review for Rolling Stone, Considering

that East West is the title of one of the best albums Paul Butterfield ever

made, it's ironic that North South should be the title of his worst.

There are not many positive reviews of North South,

and some critics seem more disappointed with the audacity of Butterfield's willingness to

deviate so far from his established persona as a blues man of great distinction.

The final nail in the coffin for his new

album is when David Fricke pens this one star review for Rolling Stone, Considering

that East West is the title of one of the best albums Paul Butterfield ever

made, it's ironic that North South should be the title of his worst.

The combination of Butterfield's blues savvy and former Al

Green producer Willie Mitchell's once magic R&B touch undoubtedly looked

good on paper. But Butterfield's singing is barely a smoky shadow of

its old husky roar. Though the artist can still blow blues harp with the

same spirit and soul he displayed he displayed in his Butterfield Blues Band

days, there simply isn't enough harmonica playing on North South to make

wading through Mitchell's anemic production, the spineless arrangements

and hopelessly lame material.

Catch a Train, Slow Down, and the nonsensical Footprints on

the Windshield Upside Down are lukewarm funk, with Butterfield and

his harp fighting a losing battle against an army of clichéd horns and

strings. The star's one harmonica showcase turns out to be a syrupy

instrumental ballad , Bread and Butterfield. And his token

blues workout is - of all things - a Neil Sedaka number, Baby Blue, which

closes the record. It's a sorry ending to a truly sad LP. The problem with album is that, it is the right

material, just recorded by the wrong artist at an inappropriate time.

In an effort to promote album sales Bearsville releases Living

in Memphis/Footprints on the Windshield Upside Down in the U.S., and they even attempt

to crack the European market with I Get

Excited (Me Excito) and Bread

and Butterfield, but nothing

gains traction. Sadly, in the minds of critics Paul Butterfield is no longer seen as a

trailblazer in American music, only an opportunistic follower of passé trends.

In spite of his doctor's advice, Butterfield does mount a

tour with a five piece band, often with his girlfriend on keyboards, even

sporting matching black t-shirts that advertize My Father's Place eatery in New

York, but even those shows are hit and miss. Similar to so many other artists

from the 60s who survive into the 80s, Butterfield is starting to feel the

financial pinch of dwindling audiences. He puts together a tightly planned one hour show that promoters

milk by taking in two audiences in one night. It is grueling way to make a

living any artist, but especially for a ill musician without a critically

acclaimed album to promote.

It is a testament to an artist's talent when people constantly

reach out to them with support for their art, but that encouragement is futile when the artist rejects it. The chronology of Paul Butterfield's mental and

physical decline seems to begin around the middle of the 70s when he loses

his artistic vision. Even the business acumen of Albert

Grossman can't seem to penetrate Butterfield's desire to self-destruct. The

obvious question is Why? Possibly, the New York's Lone Star Cafe owner Mort Cooperman shows some insight when says, Paul had the charm of a child, but he was always fighting these demons.... A

lot of people worked hard for him, because he was their hero, but he was on a

self-destructive bent. It is a frustrating and emotionally

draining dynamic that millions of families and friends experience every day. Fortunately, Butterfield's his health and

career will take a turn for the better, but unfortunately, the worst is yet to

come. Stay tuned!

It is a testament to an artist's talent when people constantly

reach out to them with support for their art, but that encouragement is futile when the artist rejects it. The chronology of Paul Butterfield's mental and

physical decline seems to begin around the middle of the 70s when he loses

his artistic vision. Even the business acumen of Albert

Grossman can't seem to penetrate Butterfield's desire to self-destruct. The

obvious question is Why? Possibly, the New York's Lone Star Cafe owner Mort Cooperman shows some insight when says, Paul had the charm of a child, but he was always fighting these demons.... A

lot of people worked hard for him, because he was their hero, but he was on a

self-destructive bent. It is a frustrating and emotionally

draining dynamic that millions of families and friends experience every day. Fortunately, Butterfield's his health and

career will take a turn for the better, but unfortunately, the worst is yet to

come. Stay tuned!